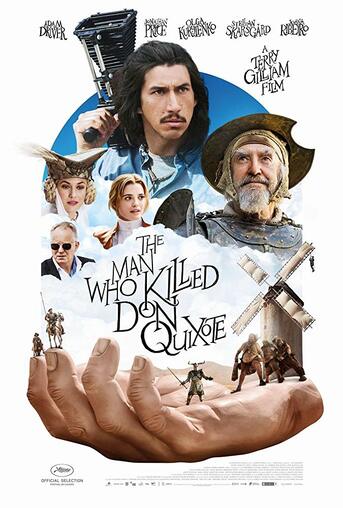

Written by Joel T. Lewis  How frustratingly appropriate it would be for me to miss the one night only premiere on account of bad weather, I thought as I embarked, braving the elements of an early spring snow storm with a name I maintain must have only been invented this year. But ‘bomb cyclone’ be damned I would make it to the theatre to see a film 25 years in the making. Terry Gilliam’s white whale, his own windmill giant, The Man Who Killed Don Quixote. Being myself a long-time Gilliam fan and particularly fond of the Lost in La Mancha documentary, I was enjoying having my own unfortunate obstacle to overcome, participating in my own small way in the grand tragedy of this film’s production. The picture La Mancha paints of a perfectly constructed disaster with every imagine-able complication rearing its ugly head in wave after wave of setbacks is almost Shakespearean: both devastating and captivating. There are moments in Lost in La Mancha, on day one of production in fact, when the unexpected roar of fighter planes passing overhead seemed to signal that the fates had declared war on Gilliam’s vision. And on the second day when rain and hail rolled washing away the crews’ equipment in it seemed that nature had added her thunderous voice to the shout of disapproval, condemning Gilliam’s mad dream. Before seeing The Man Who Killed Don Quixote I wrote the following in response to the documentary exploration of Gilliam’s failed attempt to make the film 17 years ago: The success or failure of the film will be a case of lost in translation as much as anything else and I’m not referring to the original Spanish of the source material. The film will be in essence Gilliam’s attempt to translate the vivid passion and clarity of his mind’s eye for the audience. This is what all great directors attempt but Gilliam’s surreal visions make this kind of translation all the more difficult. On the other side of having seen the film that Gilliam finally got to make, what I’m beginning to realize is that Lost in La Mancha is essentially a feature length trailer for a film that didn’t exist in 2002 and still doesn’t exist today. In a way I seem to have shot myself in the foot revisiting Lost in La Mancha so close to the premiere of the final film, though the marketing leans heavily on the audience’s fondness for the documentary. The process of detangling myself from a vision of a film in transition, of wild marionette sword fights and lumbering giants, from expecting a director’s surrealist vision which would dwarf The Imaginarium of Doctor Parnassus is one of the myriad of reasons why this review is so late in coming. It’s funny, I seemed to have taken Gilliam’s lead and shot the film in my own head and when presented with what actually came out of filming, I’m understandably underwhelmed. All of that notwithstanding, The Man Who Killed Don Quixote is an exceptional adaptation of Don Quixote if an unpolished Terry Gilliam film. The plot follows Toby, a disillusioned commercial director whose vision for a parody advertisement brings him back to the Spanish hills where he shot an adaptation of Don Quixote as a student many years before. Toby retreats from their on-location shoot to clear his head and rediscovers the village that he used for his student film. He soon discovers that his directorial influence did not benefit the locals who starred in his movie. Toby’s film gave two of its stars very different but very real delusions of grandeur which in turn have ruined their lives. First, the innocent youth Angelica (portrayed by Joana Ribeiro) persuaded by Toby’s encouragement that she ought to be a star chose a path of self-deprivation and compromise which culminated in her being treated like property by a Russian Vodka company owner, Alexei Miiskin (Jordi Mollá). And second, the aged shoemaker Javier (Jonathan Pryce), who, under Toby’s direction, became convinced that he was in fact Don Quixote de La Mancha, the Knight of chivalric legend. Toby slips between the lucid present, dreamy flashbacks, and surreal inventions of his mind as he tries to make amends for and save Angelica and Javier from the damage he caused while at the same time trying to rationalize how real Javier and his own fantasies appear as he starts losing his grip on reality.  At its core, this film is an excellent adaptation of Don Quixote with Jonathan Pryce absolutely nailing the playful and endearing madness of the titular character. Add to that the self-referential and nuanced commentary of the disruptive director’s effect on the people and places they invade while making films and you have quite the extraordinary film, but it’s in the details and the fringe commentary that Gilliam attempts where the film falls flat. There are fleeting attempts at a commentary of the international refugee crisis and the xenophobic violence and fear it has inspired across the globe but these elements are so brief and poorly integrated in the film that they seem tacked on rather than a nuanced commentary. One of the scenes in question is in particularly poor taste depicting several women in niqab pulling their face veils back to reveal long black beards eliciting the frightened scream, ‘suicide bombers!’ from the crowd. The scene is meant to play as comical as the line is dismissed out of hand, I believe in an attempt to demonstrate the ridiculousness of xenophobic stereotypes, but the screamed reaction is so disconnected from the tone of the scene that it only manages to pull the viewer out of the film. The film’s other weakness has to do with Gilliam’s female characters. While we might write off the one dimensional nature of the ‘boss’ wife’ character, and I refer to her as such as that’s about as much thought went into the writing of that character, as in the spirit of the female figures of the source material, it’s rather disconcerting that so simplistic a model wouldn’t be one of the first elements you would update and modernize when adapting Don Quixote. More troubling though is Angelica, whose character is not necessarily underwritten or one dimensional so much as she is poorly used. Angelica as the village youth given delusions of grandeur which make her comprise her values and self-worth in pursuit of the limelight, is a powerful figure. Though Toby and the audience blame Toby for sending Angelica down the less than desirable path that has led her to her current state of subservience to Alexei, she does not. Angelica owns her decisions and the path that has led to the woman she’s become showing the growth and world-weary experience of her character. But the film champions Toby as rescuer, and dismisses Angelica as victim and distressed damsel, which is tonally appropriate when dealing with the chivalric world of Quixote, but ultimately undermines the depth of Angelica as a character and effectively erases her agency in the film. From a visual perspective though, there’s not much to knock about The Man Who Killed Don Quixote. Of the three sequences in which we see a Quixote of some sort tilting at windmills, (and let’s be honest that’s the only shot that matters in a Don Quixote adaptation) the one featuring Jonathan Price’s attempt is uniquely well executed as it captures the intangible and iconic dynamic visual style of Gustave Doré’s illustrations for the novel. Trading his more signature surrealist visual style from a Parnassus or a Fear and Loathing, for landscape and natural lighting, Gilliam achieves visually stunning sequences that are among the most breathtaking he’s ever captured. A gorgeous if ultimately uneven film, The Man Who Killed Don Quixote proves that Terry Gilliam’s head is still a place I like to visit from time to time and as for the film that could have been, the one whose collapse we got to watch in real time, I suppose it’s still in the Spanish hills somewhere, forever lost in La Mancha.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

March 2025

|

|

© 2012-2025, Nerds That Geek LLC.

All Rights Reserved. |

uWeb Hosting by FatCow

RSS Feed

RSS Feed