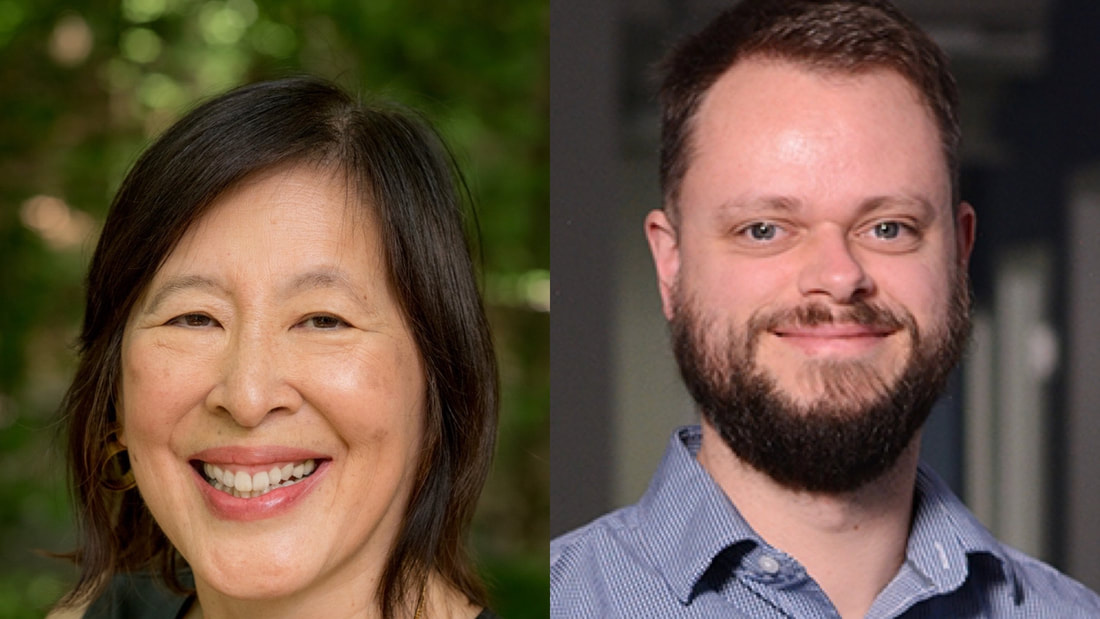

Wynette Yao & Travis Edwards, the Director/Producer & Cinematographer/Editor of ‘District of Second Chances’ Wynette Yao & Travis Edwards, the Director/Producer & Cinematographer/Editor of ‘District of Second Chances’ District of Second Chances is a poignant documentary about a concerning aspect of our criminal justice system that makes its debut on December 3, 2023, at Dances With Films. And in anticipation of its release, we here at NTG were fortunate enough to sit down with Wynette Yao and Travis Edwards, the Director/Producer and Cinematographer/Editor of this powerful film, to discuss its construction and importance. John Betancourt: I would love to know and inspire each of you to want to come to work on this project. Wynette Yao: Well, I had previously done a project for Discovery called Prison Wives. And that's the first time I realized how messed up our prison system is. And I was very distressed. And then I just went on to other projects. So, this was a chance to get back to shining a light on people who are not only forgotten, but they are looked down upon. And, of course, we're not trying to whitewash it. There are innocent people in prison, an estimated 1%. These guys, we're not saying they were innocent, you know, they were convicted of murder, and they were guilty or guilty enough, you know, they were around. And so, a lot of times those people just get dismissed, you know, but to really show these people as fully human in a way that I think we can all relate to, and then explain how, in human development, you know, when you're 19, you're a dummy. And you don't have good impulse control. And that's true of all of us, you know, no matter what we're doing. So, there was a lot of appeal to shining that light. Travis Edwards: Well, we're fortunate enough to work for FAMM (Families Against Mandatory Minimums). And so FAMM has been around for 30 years and has a large storytelling presence. And something that Wynette and I came at this, with documentary filmmaking eyes, is how do we tell a story about people who are currently incarcerated, because we're not going to get access to go into prisons or jails to film with people. And so, it just becomes incredibly difficult to show visually, you know, through the wonderful medium of film. And so, this was, I think, a way to look at the different angles of things, like we interview lawyers, we interview family members, we interview a lot of people on the outside struggling to get these guys out. And so, I think that we embraced that challenge of how do we still tell a compelling narrative while knowing that we're not going to be able to go in and, you know, spend a 10-hour day with a guy who's currently incarcerated? John Betancourt: Which brings up a follow-up question on my part. Specifically, let’s talk about all the challenges you ran into in assembling this film. Because you talk to a lot of people, some in tough spots, and that could not have been easy, and Travis you just outlined some of those challenges. Wynette Yao: Well, thank you for that question. It is always so gratifying when people can see the efforts and that they hopefully successfully overcame the obstacles. Access is just key. You know, there's a reason that we don't tend to know what's going on behind prisons, they do not let people come in easily. And it was very, very hard to communicate with the guys, when they were behind bars. You can see we had Zoom interviews, you know, and you know, how hard it is to edit Zoom interviews. “Where are the cutaways? The lighting is terrible. The audio is terrible.” So, from the production point of view, lots of challenges there. And then I think also the, you know, we're filming in the middle of Covid. And the pandemic was shutting things down sporadically. And it really it was hard enough to try and get access to some of these places. And sometimes, we had gotten in and, you know, Covid meant that, you know, we had to cancel the whole thing. Travis Edwards: Yeah, I mean, obviously, the Covid one is huge. I mean, you know, we're still we're still talking about it today. But just knowing what we were walking into, we had shoots to cancel because somebody got Covid, there was a -- I don't want to spoil it for anyone who hasn't seen it. But there's a scene later in the film that I got Covid for. It was something where there was a specific time it was happening. And so, we had to scramble and find somebody to go do it, who did a remarkable job. And just all these difficulties of you know, trying to spend time with people, were clearly exacerbated just by the limited access that we had. John Betancourt: I would love to know what invested each of you so deeply in the project to tell it in such a passionate manner. Travis Edwards: Yeah, I mean, I think it can be an extremely relatable story, because it's following largely three guys who did things when they were teenagers, we were all teenagers. And so, we all know that we all, you know, did things when we teenagers. And so just placing it there and saying that if you're 16, 17, 18 years old, that you're going to spend the rest of your life in prison, I mean, that right there if you just... if anybody thinks about how their life would have changed, if that's what happened, it's just mind blowing to me. And so, I think we really wanted to just show what that does to people, to family members, to community members, to loved ones to everybody along that trail there. Because if any of us think about what our life would be, with the amount of people that we met at age 16, onward, I mean, it's, it's incredible. And so, I think that really just trying to hone in on that human impact, and emotion is what kept us going on this. Wynette Yao: Yes, I mean, there was this whole backstory about this generation being labeled as the “Super Predators” in the 90s, you know, and it was, I remember it, it was, you know, full page ads and a national craze, that somehow this new breed of human had sprung up, and they had no conscience, and they loved to kill. And somehow, they were always black. And on the basis of that all these laws got passed, which put these guys in prison. And that whole backstory, I mean, I, I didn't really know how it came about, it was really invented, you know, but it took over the country. Unfortunately, we're still under that. Those laws are still mostly with us. And so, to have a chance at saying, “Hey, let me tell you something about how this came about, you know, that was based on some, some false premises, and let’s not go back to that,” you know, that really drove me. This idea of hoping to change a few minds that were not sympathetic, you know, and show just how human these people are, for the most part, you know, but they're totally relatable, and they can all be our friends. John Betancourt: Ultimately, what do you hope people walk away from when they watch this documentary? Wynette Yao: Yes, I really hope people walk away, saying, I believe in second chances. We should make these laws, you know, because it began with Congress in 2008, they passed the Second Chances Act, and now different states are following, but you know, it's going slowly. And so if people said, “Wow, these laws make sense. It doesn't make sense to keep people locked up at a great cost, you know, both financial and human. So, I now know what I think about this.” Travis Edwards: We have a short scene in there that didn't make in the film where it was one of the guys who is released, someone's helping him with paperwork, and she talks about how she was incarcerated. And Gene, who was the person in the scene for that one, he had to stop. He's like, “I couldn't tell you like even just today, how many people I've met, who are formerly incarcerated.” And so I think that it's just getting the change that we all are capable of and then seeing that, as Wynette said earlier, that a lot of times these are invisible stories, and so we're showing it like you know, “My goodness, you go to the grocery store, and there's formerly incarcerated people,” they're just showing us that the stigma that we put on it isn't… it's not always appropriate or helpful. And so, you're showing that people have changed, and that there's a lot of people out there with these amazing stories that we just sort of have forgotten about or tried to put in the shadows for so long. John Betancourt: What kind of change do each of you hope that this particular film inspires? Travis Edwards: Yeah, that's a big one. So, the specific laws in this film, they’re referred to as second look laws, and there's a handful of states that have adopted them. And so we're hoping that more people have the opportunity as the people in our documentary have to show that they've changed, and we're not, we're not saying open up the doors and let everybody out, we're just saying that people who put the work in these guys put in so much work, that they deserve to have the chance to, you know, have their cases looked at, and to have the opportunity to go back and be community members, family members, you know, loved ones, amazing human beings. And that's, I think, that's the hope is that we can just move the needle a little bit there. Wynette Yao: Well, you know, as you're asking these questions, I realized that one particular thing really drove me. And that is that we don't understand that long sentences don't work. Who knew? Well, all the criminologists know, you know? But it's crazy that the word has not gotten out to We the People, and particularly the lawmakers, I was wondering why it hasn't reached them. But yeah, it's pretty much proven. It's not the length of a sentence, that’s effective. What's effective is swift punishment, and the certainty of punishment. And so, if we took the resources that we spent warehousing people for decades, when they are not dangerous anymore, and put it on that kind of, you know, enforcement, law enforcement and also help, you know, like programs that help people, wow, that would actually make us a lot safer. So that's a very specific thing. But I was really like, “Oh, everyone thinks, oh, you know, throw the book at him. 20 years, 30 years, never see him”, that's not gonna do anything, and it doesn't deter crime. You know, people when they commit a crime, they're not thinking they're gonna get caught. So, they're definitely not thinking, “Oh, is it worth it? 25 years?” It just doesn't work the way we think it does. But it's such an easy thing for politicians to say, I'm tough on crime, to get votes. John Betancourt: I think one thing that I’ve started to appreciate more about documentaries, is that they can also inspire change in our local environments. What can we in both your opinions do locally to enact more change? To help with this kind of problem? Wynette Yao: Well, if you live in Washington, DC, you're lucky because two laws have already been passed, but you can continue to support them. Recently, they tried to take Second Chance further, and Congress intervened and shut it down. So, and if you live in other states, you can support those legislative efforts because they are ongoing. It's pretty simple. You can, you know, write, or call your Congressperson. You can get involved in groups that are trying to help those in prison just rehabilitate themselves, you know, there’s groups, like, there's FAMM, Free Minds, that does writing workshops. So, there’s quite a bit. Travis Edwards: Wynette did a great job of summing that up. But I think that Wynette and I also came to this project with open minds, and we learned an incredible amount on the journey. And so, I think that going at the topic of second chances and everything that entails I mean, I think that our curiosity really, was incredibly beneficial to both her and I and we're just two people. And we're hoping that more than two people will see this film and more people will become inspired and find ways they can, they can support. John Betancourt: Last question I have for both of you today, what are you each most proud of when it comes to this project? Travis Edwards: I mean, there's a lot… but I think it's interesting… I mean, from the technical standpoint, it was difficult. We filmed… it was all-natural lighting aside from sit down interviews, we didn't know what we were walking into, we didn't know what to expect in most situations. And so, the fact that we were I mean… Wynette has been an amazing resource as the director on this, to be able to tap into her expertise and knowledge and experience, it's just incredible. And so, we were able to walk into so many scenes and literally have no idea what we'd get, if there would even be a usable second of footage. And now look, you know, we have a final product. And I think just that… that confidence, being able to go in there and know that we can do it, I think is a, it's still great to watch some of these scenes. Wynette Yao: I have two things I'm proud of. The first is that I always try… I'm always conscious that people are giving you their trust, when you walk into their lives. And you, you want to be open minded. It's not that you want to advocate one way or another. But I think you want to have a good human relationship with your subjects. And I feel that, that we did that, that we respected them, while at the same time, sometimes pushing them. And the second thing is, I really am proud that Travis and I made this film as a two-person team. So many times, you know, heading out there, we were, “Oh, what are we going to do today?” It was a lot of fun, but it was our teamwork really made this possible. Because, you know, often we would have to do multiple jobs. I was the PA as well as the director and Travis was you know, the grip, and the sound person, as well as the cameraman. So, we made it work. And I'm very grateful to Travis. This interview has been lightly edited and condensed for clarity.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

March 2025

|

|

© 2012-2025, Nerds That Geek LLC.

All Rights Reserved. |

uWeb Hosting by FatCow

RSS Feed

RSS Feed