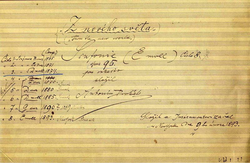

Written by Ted Author’s Note: I have always been an avid lover of classical music and performance, as well as history. The following is the beginning of a series of articles highlighting legendary composers and the influences surrounding their magnum opuses as a means to show that inspiration can be found in the most unlikely of places; from the most unlikely of sources. These inspirations were then turned into something exceptional for countless future generations to marvel over, to be swirled around and sampled delicately in our minds as a sommelier would a glass of the finest pinot noir. If you have not taken the time to listen to any of the spotlighted masterpieces or have not listened in a long while, I would strongly recommend you take the time to do so, for music is one of the most human endeavors. It elicits involuntary emotional responses that should be felt daily, be it a smile that won’t go away or tears of sadness or joy that can’t be controlled. It is when we experience these wide ranges of emotion that we feel the most alive. It will be my attempt to paint a picture of what the life and times were for those spotlighted by this series, and as such I will use unaltered quotations (where possible) from the contemporaries and the composers themselves that will bring their settings into sharper relief. To this end, some quotations used may not be of the most politically correct nature, however it is my belief that to run and hide from history is to be doomed to repeat it. Born in 1841, Antonín Dvořák was a Czech composer from the Austrian Empire. Filled with Czech nationalist pride and the political upheaval in his native Bohemia, he wrote many works inspired by “The Czech motherland”. He had admirers all over Europe such as legendary German composer Johannes Brahms and Austrian Emperor Franz Joseph I. He was innovative, influential, wildly popular, and according to musicologist and music historian Richard Taruskin, “arguably the most versatile…composer of his time.” Ironically, with the composition of Symphony No. 9 “From the New World”, Dvořák may have written the most American musical masterpiece of all-time. At the time of the composition of “From the New World”, Dvořák had been living in New York City during a three year stint working as the director of the National Conservatory of Music located there. It was in 1893 that the New York Philharmonic commissioned the creation of what would become his ninth symphony, and unbeknownst to all, his greatest work and one of the most celebrated classical pieces of all time. Drawing from many influences, including the styles of Ludwig van Beethoven and Franz Schubert, the greatest of his inspirations were the wide open spaces of the American landscape, and the people found there, particularly of Black and Native American descent. While it is unclear exactly when and where Dvořák first encountered Native American music and culture, it is possible that his first exposure came in 1879 when a travelling group of Iroquois Indians came to Prague in a show to demonstrate horseback acrobatics, archery skills and tribal music and dances. It is also possible that while composing his ninth that he attended one of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Shows in while in New York, which was contained performances by Oglala Sioux tribe members. In an article written by Dvořák, he stated: “I have not actually used any of the [Native American] melodies. I have simply written original themes embodying the peculiarities of the Indian music, and, using these themes as subjects, have developed them with all the resources of modern rhythms, counterpoint, and orchestral colour.” What is known to be influential to Dvořák, however, was Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s epic poem, “The Song of Hiawatha”, whose influence can be felt all throughout the score, and in the third movement particularly. Dvořák wrote that this scherzo had been "suggested by the scene at the feast in Hiawatha where the Indians dance".  What is much clearer to historians is the beginnings of the Black American influences. While at the National Conservatory of Music, he encountered a black student and future composer by the name of Harry T. Burleigh who would sing to Dvořák traditional spirituals. Burleigh would later say that Dvořák had become engrossed with the “spirit” of these melodies before setting out to write his own. As was proclaimed by Dvořák: “I am convinced that the future music of this country must be founded on what are called Negro melodies. These can be the foundation of a serious and original school of composition, to be developed in the United States. These beautiful and varied themes are the product of the soil. They are the folk songs of America, and your composers must turn to them.” These influences are also felt throughout the piece, in particular with a flute solo in the first movement that brings “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot” to mind. With the influences of Native and Black American cultures in mind, Dvořák sought to blend these with the styles of two great European masters. Ludwig van Beethoven’s influences can be heard predominantly in the first and fourth movements of “From the New World”, with the allegros being reminiscent of the controlled frenzy of Beethoven’s Symphony No. 5 in C minor or Symphony No. 9 in D Minor (The Choral), both legendary in their own right. The adagio second movement and scherzo third movements are written with the tranquillity and grace similarly found in Franz Schubert’s Great C Major Symphony. As with his other influences, Dvořák did not set out to emulate Beethoven or Schubert directly, but to rather to capture the essence of that which made their works unique, and then bind them together with the sinews of American culture. Upon Symphony No. 9’s completion, Dvořák’s magnum opus debuted at Carnegie Hall on 16 December 1893 to tumultuous applause between every movement, compelling Dvořák to oblige the crowd by standing and bowing each time. This would be the greatest success of his musical career, and shortly thereafter the piece was published and seized upon by eager conductors around the world for performance. In 1894 “From the New World” was first performed by the London Philharmonic Society and quickly became one of their most popular ever since. It has found its way into modern popular culture, turning up in television, films, anime, and video games. Ultimately, the piece was taken further than any other symphony had travelled: aboard Apollo 11 by astronaut Neil Armstrong for the first moon landing. As Dvořák’s works were published in Europe during his American sojourn, the proofs were being corrected by Johannes Brahms before final publication. For a man of Brahms’ stature, this would have been a laborious task, and Dvořák marvelled at it, saying it was difficult to understand why Brahms should "take on the very tedious job of proofreading. I don't believe there is another musician of his stature in the whole world who would do such a thing." To listen to any of Dvořák’s works, however, is to understand why Brahms would consider Dvořák to be a worthy contemporary; “From the New World” only further cements Dvořák’s legacy of one of the all-time greats - an Old Master. Its movements rise and fall in a tide of emotion and fervor that tug at the heart-strings and inspire greatness. They recall the peace of a sunrise over the Great Plains to begin a beautiful summer’s day and bring solace to an aching heart, or fill an aspiring mind with passion. Dvořák’s greatest gift in the composition of this piece, whether he intended it or not, was to show the world that music is the great unifier. “From the Free World” was a multi-national effort, merging the Old World, the New World, and their peoples together as one for a brilliant composition filled with hope and compassion. Though its roots may stem from the minority, there is no distinct “boundary” between these influences and that of its traditional European styles. It is a fusion that represents what we all are: one people, woven together like the instruments in a symphony.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

August 2024

Categories |

|

© 2012-2025, Nerds That Geek LLC.

All Rights Reserved. |

uWeb Hosting by FatCow

RSS Feed

RSS Feed