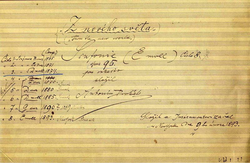

Written by Ted Author’s Note: I have always been an avid lover of classical music and performance, as well as history. The following is the beginning of a series of articles highlighting legendary composers and the influences surrounding their magnum opuses as a means to show that inspiration can be found in the most unlikely of places; from the most unlikely of sources. These inspirations were then turned into something exceptional for countless future generations to marvel over, to be swirled around and sampled delicately in our minds as a sommelier would a glass of the finest pinot noir. If you have not taken the time to listen to any of the spotlighted masterpieces or have not listened in a long while, I would strongly recommend you take the time to do so, for music is one of the most human endeavors. It elicits involuntary emotional responses that should be felt daily, be it a smile that won’t go away or tears of sadness or joy that can’t be controlled. It is when we experience these wide ranges of emotion that we feel the most alive. It will be my attempt to paint a picture of what the life and times were for those spotlighted by this series, and as such I will use unaltered quotations (where possible) from the contemporaries and the composers themselves that will bring their settings into sharper relief. To this end, some quotations used may not be of the most politically correct nature, however it is my belief that to run and hide from history is to be doomed to repeat it. Born in 1841, Antonín Dvořák was a Czech composer from the Austrian Empire. Filled with Czech nationalist pride and the political upheaval in his native Bohemia, he wrote many works inspired by “The Czech motherland”. He had admirers all over Europe such as legendary German composer Johannes Brahms and Austrian Emperor Franz Joseph I. He was innovative, influential, wildly popular, and according to musicologist and music historian Richard Taruskin, “arguably the most versatile…composer of his time.” Ironically, with the composition of Symphony No. 9 “From the New World”, Dvořák may have written the most American musical masterpiece of all-time. At the time of the composition of “From the New World”, Dvořák had been living in New York City during a three year stint working as the director of the National Conservatory of Music located there. It was in 1893 that the New York Philharmonic commissioned the creation of what would become his ninth symphony, and unbeknownst to all, his greatest work and one of the most celebrated classical pieces of all time. Drawing from many influences, including the styles of Ludwig van Beethoven and Franz Schubert, the greatest of his inspirations were the wide open spaces of the American landscape, and the people found there, particularly of Black and Native American descent. While it is unclear exactly when and where Dvořák first encountered Native American music and culture, it is possible that his first exposure came in 1879 when a travelling group of Iroquois Indians came to Prague in a show to demonstrate horseback acrobatics, archery skills and tribal music and dances. It is also possible that while composing his ninth that he attended one of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Shows in while in New York, which was contained performances by Oglala Sioux tribe members. In an article written by Dvořák, he stated: “I have not actually used any of the [Native American] melodies. I have simply written original themes embodying the peculiarities of the Indian music, and, using these themes as subjects, have developed them with all the resources of modern rhythms, counterpoint, and orchestral colour.” What is known to be influential to Dvořák, however, was Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s epic poem, “The Song of Hiawatha”, whose influence can be felt all throughout the score, and in the third movement particularly. Dvořák wrote that this scherzo had been "suggested by the scene at the feast in Hiawatha where the Indians dance".  What is much clearer to historians is the beginnings of the Black American influences. While at the National Conservatory of Music, he encountered a black student and future composer by the name of Harry T. Burleigh who would sing to Dvořák traditional spirituals. Burleigh would later say that Dvořák had become engrossed with the “spirit” of these melodies before setting out to write his own. As was proclaimed by Dvořák: “I am convinced that the future music of this country must be founded on what are called Negro melodies. These can be the foundation of a serious and original school of composition, to be developed in the United States. These beautiful and varied themes are the product of the soil. They are the folk songs of America, and your composers must turn to them.” These influences are also felt throughout the piece, in particular with a flute solo in the first movement that brings “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot” to mind. With the influences of Native and Black American cultures in mind, Dvořák sought to blend these with the styles of two great European masters. Ludwig van Beethoven’s influences can be heard predominantly in the first and fourth movements of “From the New World”, with the allegros being reminiscent of the controlled frenzy of Beethoven’s Symphony No. 5 in C minor or Symphony No. 9 in D Minor (The Choral), both legendary in their own right. The adagio second movement and scherzo third movements are written with the tranquillity and grace similarly found in Franz Schubert’s Great C Major Symphony. As with his other influences, Dvořák did not set out to emulate Beethoven or Schubert directly, but to rather to capture the essence of that which made their works unique, and then bind them together with the sinews of American culture. Upon Symphony No. 9’s completion, Dvořák’s magnum opus debuted at Carnegie Hall on 16 December 1893 to tumultuous applause between every movement, compelling Dvořák to oblige the crowd by standing and bowing each time. This would be the greatest success of his musical career, and shortly thereafter the piece was published and seized upon by eager conductors around the world for performance. In 1894 “From the New World” was first performed by the London Philharmonic Society and quickly became one of their most popular ever since. It has found its way into modern popular culture, turning up in television, films, anime, and video games. Ultimately, the piece was taken further than any other symphony had travelled: aboard Apollo 11 by astronaut Neil Armstrong for the first moon landing. As Dvořák’s works were published in Europe during his American sojourn, the proofs were being corrected by Johannes Brahms before final publication. For a man of Brahms’ stature, this would have been a laborious task, and Dvořák marvelled at it, saying it was difficult to understand why Brahms should "take on the very tedious job of proofreading. I don't believe there is another musician of his stature in the whole world who would do such a thing." To listen to any of Dvořák’s works, however, is to understand why Brahms would consider Dvořák to be a worthy contemporary; “From the New World” only further cements Dvořák’s legacy of one of the all-time greats - an Old Master. Its movements rise and fall in a tide of emotion and fervor that tug at the heart-strings and inspire greatness. They recall the peace of a sunrise over the Great Plains to begin a beautiful summer’s day and bring solace to an aching heart, or fill an aspiring mind with passion. Dvořák’s greatest gift in the composition of this piece, whether he intended it or not, was to show the world that music is the great unifier. “From the Free World” was a multi-national effort, merging the Old World, the New World, and their peoples together as one for a brilliant composition filled with hope and compassion. Though its roots may stem from the minority, there is no distinct “boundary” between these influences and that of its traditional European styles. It is a fusion that represents what we all are: one people, woven together like the instruments in a symphony.

0 Comments

Written by Ted There are few things I enjoy more than sitting back in a dark room with a vinyl copy of Pink Floyd's Dark Side of the Moon blasting away on a fine set of stereo speakers and drifting away to the furthest recesses of my mind. No matter how many times I listen to it, there's always a subtle nuance I missed in the previous listenings. Being one of the greatest albums of all time, Dark Side is in a league of its own - as most Floyd albums are. As much as I love jamming out to Floyd and their timeless music, it wasn't just their songs that made them one of the greatest bands of the 20th century. What sets Floyd apart from nearly every other group is their live show. The lasers, the stunning lighting and visuals, and above all, their dedication to give the audience an absolutely mind-bending experience. This concept is exactly what Floyd understood better than nearly anyone: that the live performance is the perfect way to give back to their fans, to say "Thank you for the support, now sit back and enjoy exactly what that means to us". More than its use as a way to give back to fans, one of the most critical elements to the live performance is that it reminds us that artists are human. Studio albums are easy to listen to because they're "mistake free". A great producer can easily correct the blemishes of the artist, so much so, that on the truly great albums it's impossible to know where the artist ended and the producer began. Truly, these masterpieces are a joy to behold. However, when you hear your favorite musician give it a go without the safety net of multiple takes and a talented producer, it becomes easy to glimpse the human behind the music, definitively showing the heart and soul that has been put into their craft. This, above all, demonstrates the artist’s willingness to connect with their audience. Additionally, live performance exposes when an artist is just going through the motions. It’s all too common for an artist to be late to their own show (looking at you, Justin Bieber) and seemingly not to give a rats about their fans (still looking at you, Biebs). The worse offense is hitting the stage too drunk to remember the words or be so high that only dogs can hear them. In a perfect world, concert goers would receive a full refund if they were in attendance of such a show. Conversely, like Pink Floyd, there are artists that achieve another plane of being with their live performances. Grammy-winning Bon Iver, an indie project band founded by the talented Justin Vernon, delivers live shows that are specifically meant to capture the audience’s rapt attention by delivering new arrangements on many of their songs. It is live that the audience comes to the stunning revelation that their songs, such as the hit Skinny Love, were meant to be sung as loudly as possible, by as many people as possible, and in as in an intimate setting as possible. Moreover, Vernon and his gifted cadre of multi-instrumental musicians have set about making sure that with each venue in which they perform, the audience - regardless of its size - will feel that intimacy, that connection to the music as Bon Iver does. When discussing Skinny Love In an interview with Pitchfork, Vernon was quoted as saying, “"I don't want to be the guy with an acoustic guitar singing songs, because that's boring for the most part. The song actually needs 80–500 people singing or whatever the vibe is of that room, it needs that fight.” To that end, Bon Iver delivers with each live performance a high quality version of their catalogue that is unlike anything found on the studio albums. New instruments and vocals will be woven in, or taken out and replaced by a simple stomp-clap arrangement by the 9-member band. They may ramp up the energy on a song that previously may have been a perfect fit to a sombre mood on a snowy day, without taking away any of its feeling. Above all, they encourage the audience to belt out the songs, to connect, to feel, and go home with a head full of beautiful music that will likely not be duplicated for another audience, but rather reinvented.  With apologies to the generic, run-of-the-mill lip-syncing pop star, this is one of the great failings of that genre. Sure, they may put on a sexy, elaborate stage show with costumes and pageantry, but odds are that the song heard on stage will be identical to the one their fans bought on iTunes. There likely won’t be that extra twist, that guitar solo that gets stretched for days, or that really well known song that gets turned on its head, just to keep the crowd guessing. When the lead singer’s voice starts cracking with emotion because they, like their audience, are completely wrapped up in the song - these are the things that create nostalgic memories cherished for a lifetime. I humbly submit my hypothesis that this is one of the top reasons that pop music doesn’t endure the long count of years as well: the personal connection to the listener just isn’t there. Simply put, the live show is the measure of an artist, the gold standard that separates a talented musician from being merely a performer. It’s not even that hard to tell them apart; for many performers, their music is written by some ghostly song-writer no one could recognize on the street. The connection to the emotion of the material is only incidental; the song is not a conduit of their raw emotion and experiences. Or perhaps they’re just trying to catch the coat-tails of a fad, full of catchy riffs but bereft of substance and authenticity. When an artist becomes a musician, they will put on a show to remember them by, one that will show you their heart, soul, talent, and above all, appreciation of those who come in droves to see them play. It’s what Pink Floyd has shown its fans through the decades; what Bon Iver strives to do every time they take the stage. It’s what makes a musician, and us, feel human. |

Archives

August 2024

Categories |

|

© 2012-2025, Nerds That Geek LLC.

All Rights Reserved. |

uWeb Hosting by FatCow

RSS Feed

RSS Feed