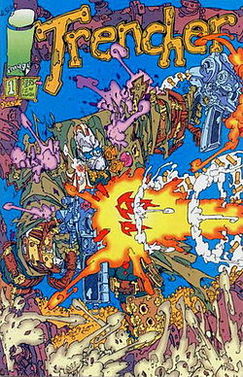

Written by Joel T. Lewis If you've read any of my previous articles on comics you know that I subscribe to judging a comic book by its cover. My bent and paper-cut fingers rifle through scores of backed and boarded issues and I stop: captivated by a color scheme, a brooding figure, or, in the case of Trencher, utter bedlam. Image was a different ball game when it came to comics especially in the early 90’s. Content creators had their character’s copyrights, creative control, and could operate independent of corporate big-wigged fingers in their comic’s pie. Image produced unique comics like Spawn and the Savage Dragon, and churned out characters like Shadowhawk and Supreme who were more reminiscent of Marvel and DC properties. Trencher is a property that did not have the staying power of Spawn, Supreme, or the Savage Dragon, but it is a good example of the freedom that a creator had in the early years of Image Comics. Whether the results of that freedom are brilliant or misguided is a question I have not settled when it comes to Trencher. Trencher is an exterminator of sorts. He sends wrongfully reincarnated souls back to Hell after scenery smashing combat in which both he and his prey leave bits and pieces of themselves in bloody heaps all over the panels. Trencher has an impressive healing factor and a sassy Dispatcher’s voice wired into his head as he goes after a thug with vine-like nose hair, a vomit-themed creature called the Hurler, and four separate reincarnations of Elvis Presley. Trencher is as wacky, violent, and gross as you could hope for however, the artwork and the style of narration of the issues make the comic unreadable. The first issue is so overwhelming and cacophonous that the eye is fatigued within the first few panels as cityscape and hero-villain violence meld and twist into indecipherable soup. You cannot track Trencher from panel to panel: as he tumbles and fractures, spilling flesh, blood, and wreckage all over the pages you're never sure of his position or which direction the next blow is coming from. At first I thought that I was just too tired to decipher what artist Keith Giffen intended for me to see on the page so I closed the first issue a few pages in and got some sleep. The following day I returned to find that Trencher was just too over-stimulating to process. I did endure long enough to read all four issues in the Trencher series and to his credit, Giffen tones his style back a few clicks with each issue, making the fourth of the series much more accessible. This dialing back came too little too late as the fourth issue was to be the last of the Trencher series and to be honest, I'm not sure if I could have powered through a fifth. Trencher is a comic like no other that I've ever read: one whose artwork overwhelmed any attempt at narrative clarity. Not that narrative clarity is absolutely necessary to enjoy a comic but even when a narrator is unreliable or a storyline is unclear, it shouldn't be impossible to discover what the story is because of the artwork. Though they inspired this reaction from me, I treasure my issues of Trencher. No comic has made me think more deeply about how I read comics, why I enjoy comics, and to what lengths I'll go trying to find purpose and clarity in a comic.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

May 2024

|

|

© 2012-2024, Nerds That Geek LLC.

All Rights Reserved. |

uWeb Hosting by FatCow